Peering toward past and future wonderlands of extended reality.

“Books are the original Virtual Reality.” Marushia Dark

“Imagination is the only weapon in the war with reality.” Lewis Carroll

“Today, we’re either at the beta or VHS version of VR. And we’re not totally clear whether it’s the computer, or the fax machine.” Jessica Lindl, VP of Social Impact and Education at Unity

“When Virtual Reality gets cheaper than dating, society is doomed.” Scott Adams

“Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a persistent one.” Albert Einstein

Arizona Cardinals Quarterback Kyler Murray made headlines last summer when his record-breaking $230 million five-year contract had a “homework” clause in it. Despite the 25-year-old quarterback’s accomplishments on the field, (Heisman Trophy winner, NFL Rookie of the Year, etc), the guys writing the checks felt like #1 needed to be watching more film.

Four hours of watching film a week from pre-season thru the last game, or the contract was null-and-void.

Coaches and quarterbacks are notaries for watching mind-numbing amounts of video of opponents to get an edge on their competition. In fact, during the football season, it’s not unusual for coaches to have mattresses in their offices, as they are viewing film into the wee hours of the night. Peyton Manning was said to watch 20 hours of film a week to prepare for game day.

While Kyler clearly didn’t have a thing for watching football film, he is a gigantic video gamer. In fact, he’s logged 1328 hours on Call of Duty and played 4500 matches. Cardinals fans became concerned when a statistical sleuth showed how Murray’s production dropped whenever Call of Duty had a “Double XP” weekend, with the thesis being that’s how he was spending his time versus figuring out when the Bears may blitz or not.

When Murray came off the field screaming at his Head Coach Kliff Kingsbury on Thursday Night Football, some speculated it was caused by anxiety about missing out on the new release of Call of Duty.

While you would think Kyler had 230 million reasons to be motivated to be watching film, the fact he was spending a significant part of his free time playing a video game suggests to me maybe the problem isn’t with Kyler Murray but how we engage people to learn. Doing something you want to do trumps what things that you have to do for most people.

Two of GSV’s mega themes are “Hollywood Meets Harvard” and “Invisible Learning”… making learning more fun and natural. Moreover, given the statistically shorter attention span of Gen Z, learning should look more like TikTok than textbooks.

Arguably, the top Virtual Reality expert in the world is Jeremy Bailenson out of Stanford. A handful of years ago, I visited Strivr, a Virtual Reality company he co-founded. Amongst various programs Strivr had created, one was for quarterbacks where they were able to simulate what it was like to have a live defense against you.

Real time, you could analyze the defense, make decisions based on reads you made on the fly, and see how those decisions resulted in effectiveness. Having been someone who had watched thousands of hours of film, I understood immediately how much more effective, efficient and fun this would be. Truly, a game changer.

In keeping with our Arizona dream theme, this Friday, ASU released dramatic learning results from its pioneering project using VR biology labs.

Led by Hollywood producer Walter Parkes (Men in Black, Minority Report), ASU’s Michael Crow, and CEO Josh Reibel, Dreamscape Learn is creating immersive classrooms with VR headsets and courseware that combine emotional narrative with hands-on learning.

Led by Hollywood producer Walter Parkes (Men in Black, Minority Report), ASU’s Michael Crow, and CEO Josh Reibel, Dreamscape Learn is creating immersive classrooms with VR headsets and courseware that combine emotional narrative with hands-on learning.

It’s “Hollywood Meets Harvard” in a big way. Walter Parkes and Steven Spielberg partnered to create Dreamscape Learn’s first classroom experience, Alien Zoo, which imagines a sanctuary in space for endangered alien species. Designed to replace conventional lab work for Introductory Biology, students step into the shoes of a field scientist and perform scientific investigations that would be otherwise inaccessible to someone without an advanced degree…and astronaut training.

In an earlier pilot at ASU, the Alien Zoo modules demonstrated an 18% increase in knowledge retention after a single one-day session. That’s equivalent to a two-letter-grade improvement. Students were more engaged, earned better grades, and helped each other more often than those who didn’t participate in the VR lab. These results encouraged ASU to include Dreamscape Learn lab courses in all introductory biology courses by spring 2023.

To reach a wider audience, the firm released a 2D cloud-streaming version targeting target online learners who are unable to attend the 3D haptic pods at ASU. At-home headset experiences will come next, bringing a revolutionary new way to teach science to all learners.

Other educational institutions want to enter the Zoo as well. Utah’s Board of Education signed a contract with Dreamscape Learn worth $3.2 million, writing that “this transformational technology has proven learning outcomes and student satisfaction, which affords a new opportunity in the teacher toolkit to close gaps for students with a one-of-a-kind VR platform.”

There remain key areas of friction. The level of coding required to create content is still prohibitive to most users — no-code tools will be the unlock. The hardware remains inaccessible for most, and connectivity isn’t quite there to enable widespread usage.

But five years from now, we envision a major shift in learning, from passive to engaged and motivated learning. The role of teachers will change, from knowledge delivery to facilitation.

A study from PWC and Talespin had a number of “WOW” findings about VR training:

VR learners required less time to learn: VR-trained employees completed training up to 4x faster than classroom learners, and 1.5x faster than e-learners.

VR learners demonstrated higher confidence in what they learned: VR-trained employees were 275% more confident to act on what they learned after training — a 40% improvement over classroom learners, and a 35% improvement over e-learners.

VR learners had a stronger emotional connection to training content: VR-trained employees felt an emotional connection to training content that was 3.75x greater than classroom learners, and 2.3x greater than e-learners.

VR learners were more focused: VR-trained employees were 4x more focused during training than their e-Learning peers, and 1.5x more focused than classroom learners.

VR learning is more cost-effective: Above 375 learners, VR training costs less than classroom learning. Above 1,950 learners, VR training costs less than e-learning.

2020 was the inflection point when society realized its urgent need to provide first-class digital education. Dreamscape Learn recognizes this and is creating environments where learners can be more capable and empowered than ever before.

We’re very excited by what we’re seeing in the development of the overall market, and specifically the success of ASU and Dreamscape Learn. However, the history of VR, AR, and MR have left us in a “cold shower mode” before. When Pokemon Go had 50 million participants within the first 19 days, the fastest adoption of a new technology ever, I thought it was the starting gun going off for the virtual/augmented space, which had been long on promise and short on results since people started talking about it.

We wanted to take a step back and ask: where did XR come from, and what drove its adoption (or lack thereof)? Let’s take a look at the history to see what the future may hold for this game-changing technology.

Extended Reality’s Ancestors

The predecessor of virtual reality can be traced back to nineteenth-century stereoscopes. Sir Charles Wheatstone invented the Victorian gadget in 1838, which combined two photographs of the same object taken from different points of view, giving the image a sense of depth and immersion.

The moving image was the other major advancement in immersion. In 1895, the Lumiere Brothers’ “Arrival of a Train” depicted a train approaching the audience, causing them to scream and flee.

The Link Trainer was invented in 1935 to provide pilots with a safer, more realistic way to practice flying. Link Trainer provided pilots with the sensation of being in a plane cockpit, allowing them to experience various flight conditions such as turbulence and instrument malfunctions. The simulator trained 500,000 US pilots for WWII.

“Pygmalion’s Spectacles,” a 1936 science fiction story by Stanley Weinbaum, tells the story of virtual reality long before the term was coined. The protagonist discovers a pair of goggles that transport him to a virtual world where he can see, hear, and touch whatever his imagination desires.

It was an early tale that laid out the future for virtual reality. As Weinbaum wrote,

“But listen — a movie that gives one sight and sound. Suppose now I add taste, smell, even touch, if your interest is taken by the story. Suppose I make it so that you are in the story, you speak to the shadows, and the shadows reply, and instead of being on a screen, the story is all about you, and you are in it. Would that be to make real a dream?”

Ground Floor of VR

One of the earliest ways to experience virtual reality was Sensorama, developed in 1956 by cinematographer Morton Heilig. It used a stereoscopic display within a theater cabinet device and included fans, stereo-sound, and even odor emitters to simulate the noise and smells of riding a motorcycle through New York.

Heilig was unable to obtain financial backing for his visions and patents. But he came back again with another product, the Telesphere Mask. It was the first example of a head-mounted display. The mask featured a video screen for each eye, allowing the user to “watch TV” with full peripheral vision and binaural sound, without any motion tracking or interactivity.

In 1961, Philco engineers Comeau and Bryan created a head-mounted display that follows head movements to correspond with a remote video camera system. This pioneering technology lacked computer simulation, and it was applied by the military for immersive remote viewing of dangerous situations.

In 1965, Professor Ivan Sutherland explained his concept of the “Ultimate Display,” where users could interact with objects in the hypothetical world.

“The ultimate display would, of course, be a room within which the computer can control the existence of matter. A chair displayed in such a room would be good enough to sit in. Handcuffs displayed in such a room would be confining, and a bullet displayed in such a room would be fatal. With appropriate programming such a display could literally be the Wonderland into which Alice walked.”

In 1968, Sutherland invented the Sword of Damocles, one of the first stereoscopic HMD. Connected to a computer and suspended from the ceiling (hence the name), the device allowed users to view computer-generated graphics and manipulate them with a keyboard or joystick. It offered true immersion, allowing users to view graphics all around them rather than just straight ahead.

VR’s First Wave

By the 1970s, virtual reality was becoming more than just an idea. In 1972 GE built one of its first flight simulators for use by Navy pilots; it featured 180-degree projections that provided them with a complete view around their plane as they flew through missions.

A few years later in 1976, Myron Krueger created what is now known as augmented reality when he introduced his Videoplace system at a lab at the University of Connecticut. It used projectors alongside video cameras into various rooms, creating 3D environments and on-screen silhouettes. Users could interact digitally within those worlds while still being able to see each other real time from anywhere inside.

The first wired glove, the Sayre Glove, was developed in 1977 by Richard Sayre at the University of Illinois as a project for the National Endowment for the Arts. It used light-based sensors to measure finger movements.

By the late 70s, the military was becoming interested in virtual reality. One of the early projects was the VITAL helmet, made by McDonnell-Douglas in 1979. The head tracker allowed pilots to see realistic images of the outside world, which was marketed to bring “greater visual power to a wider range of training challenges.”

Three years later, military engineer Thomas Furness developed a prototype for the Visually Coupled Airborne Systems Simulator (VCASS). Pilots wore a “Darth Vader helmet” which augmented the out-of-sight window views with graphics describing targets and flight paths, landmarks and hazards. With 1-inch diameter CRTs with four times the resolution of a typical TV set at the time, virtual environments immersed the pilot in a symbolic world.

Impressed, the Air Force really got behind Furness’s Super Cockpit program back in 1986. Furness described it as a system where you “put on a magic helmet, magic flight suit, and magic gloves.” With an HMD equipped with voice-controls, 3D sound and sensors, virtual hand controllers, and an eye control system, the Super Cockpit provided natural and intuitive interfaces for pilots to control fighter jets.

In 1984, Jaron Lanier founded VPL Research, one of the first companies to develop and sell virtual reality products. Coining the term “virtual reality,” Lanier launched wearable sensor products including the DataGlove and the DataSuit, as well as a head-mounted display called the EyePhone, the first commercially available VR headset.

The full setup, complete with a PC setup and video control unit could be purchased for a smooth $250,000. Few were able to afford it and the company filed for bankruptcy in 1990. But the products and ideas behind VPL would become popularized by the 1992 techno-thriller film The Lawnmower Man.

Based on the $10,000 DataGlove, Mattel produced the $75 Power Glove to market as a controller for the Nintendo Entertainment System. It sold 100,000 units worldwide, but gamers were unimpressed with its imprecise and difficult-to-use controls.

NASA got in on the action with the development of the Virtual Interface Environment Workstation (VIEW) in 1989. VIEW partnered with VPL to implement the DataGlove to allow users to grasp virtual objects, issue commands with gestures, and fly through the environment.

The VIEW lab was intended for a range of space station applications like simulating planetary exploration. NASA also experimented with remote surgical operations to be carried out on astronauts by robots, but these tests were abandoned due to the delay in transmitting information.

In the first wave of VR, technology was costly, heavy and lacked visual immersion. Computers would need to speed up to allow head movements to be rendered in 3D virtual worlds. But early VR systems by the government and researchers demonstrated applications in entertainment, research and training.

VR’s Second Wave

Through the late 1980s and 1990s, numerous VR projects were founded to reach the commercial audience. VR arcades and simulators that combined attributes of video games, amusement park rides, and highly immersive storytelling.

Early successes include Disneyland’s Star Tours, a flight simulator ride based on the Star Wars movies; and the Virtuality Group Arcade Machines, launched in 1991 and found in video arcades with headsets, joysticks, and multiplayer functionality.

In 1991, Sega announced a VR headset for a price point of $200. The device never launched due to technical difficulties. User testing revealed that it caused motion sickness and headaches. It never launched.

Sega debuted VR-1 the following year, an arcade motion simulator that moves in sync with what’s happening within the HMD. Featured in SegaWorld amusement parks, critics noted its graphics were worse than other arcade games, and it was eventually dismissed as a gimmick.

In 1995, Nintendo launched the Virtual Boy, the first portable console capable of displaying 3D images. Like the Power Glove, it flopped, as consumers found it uncomfortable to use and its lack of color in graphics unappealing.

There was an alternative to head-mounted displays — Projection VR, AKA the CAVE (Cave Automatic Virtual Environment). It was invented by Carolina Cruz-Neira in 1992 and featured a 10x10’ video theater in a room with projector screens. It was designed as a tool for scientific visualization and had the advantage of offering users freedom of movement within a room.

In 1992, the first VR movie was released, Angels. Created by Nicole Stenger, a research fellow at MIT, viewers could experience love encounters by touching the hearts of the Angels in a carousel.

In 1992, Boeing Aerospace researchers, Tom Caudell and David Mizell coined the term “augmented reality” in the field of aircraft manufacturing.

Augmented reality hit the theater in 1994 with the stage performance Dancing in Cyberspace. Created by Julie Martin and sponsored by the Australia Council for the Arts, the show featured dancers engaging with virtual objects.

In 1999, Hirokazu Kato of Nara Institute of Science and Technology developed ARToolKit. Released in 2001 by the University of Washington’s HIT Lab, it was the first open-source library for AR developers to track and overlay virtual graphics onto the real world and one of the first AR SDKs for mobile. In 2005, HIT released AR Tennis as the first application of AR on mobile devices, run on Nokia phones.

There was limited development in VR and AR after the boom of the 1990s. That is, with the exception of Google Street View, released in 2007. Street View went 3D in 2010 — a large step toward the creation of a ‘digital twin’ of the world.

Meta’s Metaverse

After a decade of disinterest, the 2010s saw an explosion in development and momentum. Google, Microsoft, HTC, Sony and hundreds of other companies rushed in.

Companies like Magic Leap raised a whopping levels of funding — $3.5 billion since 2010. But they were too early. The hardware wasn’t ready, and they lacked the content to create a valuable experience.

There were successes, though. Snapchat Lenses popularized AR across the social web, and Pokemon Go became the fastest mobile game to hit 50 million worldwide downloads — taking just 19 days. Since 2016, Pokemon Go has accumulated over a billion global downloads and generated $4.5 billion in revenue.

Meta’s announcement last week caps off a 10 year journey for the company’s VR ambitions, starting with Oculus, which first announced its Kickstarter campaign for its initial prototype on August 1, 2012. The campaign raised $1 million in funding in less than 36 hours.

In March 2014, just over 18 months after the Kickstarter campaign, Facebook announced that they would acquire Oculus for $2 billion. Over the following years, Oculus released a variety of products into the market, including the Oculus Rift, Go, Quest, and Quest 2.

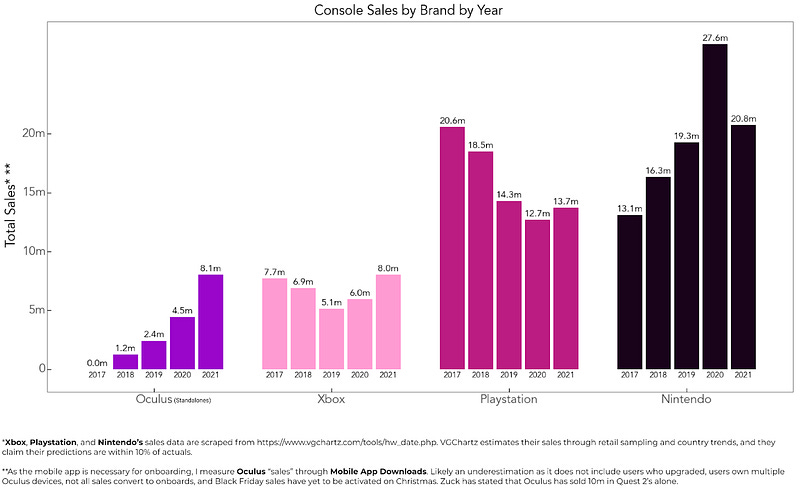

Oculus Quest was the first standalone headset that contained the capabilities of a mobile phone. While initial adoption was slow, VR hit an inflection point in 2021: more Oculus headsets were sold than Xbox consoles.

In August 2020, Facebook announced the formation of Reality Labs, a business unit that encompasses all of Facebook’s VR, AR, and Metaverse efforts (and that Meta would spend $10 billion on these efforts over the next year).

Soon afterwards in October 2021, Facebook announced their rebrand to Meta, introduced “Project Cambria”, and phased out the “Oculus’’ brand. Facebook wasn’t just making headsets; they were reorienting (and risking) their entire business around the migration to the metaverse.

One year and $10 billion later brings us to Meta’s announcement of the Meta Quest Pro. While previous iterations of Meta’s VR headsets were focused on casual and immersive use cases (e.g. gaming), the Quest Pro is positioned as a tool for the enterprise.

Who is the target enterprise consumer? The 200 million people who buy new PCs for their work each year (and the 350 million people still using Zoom meetings). While Meta has been creating VR hardware for 5+ years, they are now creating a VR ecosystem to build out the industrial metaverse, starting with knowledge workers.

While Meta’s hardware grabs headlines (and makes memes), their software partnership with Microsoft is just as important. Meta is partnering with Micorosft to bring Teams, Office, Windows, and Xbox Cloud Gaming to Meta’s Quest VR headsets.

The “Pro work line” is targeting high-end professionals and knowledge workers who are willing to pay $1,500 for a device that can increase productivity, collaboration, and creativity. As Satya Nadella claims, “we are clearly going through a once-in-a-lifetime change in how we work.” Meta and Microsoft are betting that what the desk was to the original knowledge economy, the headset will be to knowledge economy 2.0.

Early reviews of the Quest Pro give traction to Zuckerberg’s claims. As Zuckerberg puts it, the Quest Pro can instantly give anyone their perfect workstation, anywhere you go, whether you’re at home, Starbucks, or on a bus. Additionally, the device brings facial expression detection, “shockingly precise” controllers, and virtual meeting rooms that actually feel like a room.

This process of creating the “enterprise metaverse” has already started: Accenture has already distributed 60,000 Quest 2 headsets to its employees. But Meta’s target market is much larger than just accountants and consultants: it’s 2.7B deskless workers, 80% of the global workforce.

If VR does represent the next computing platform, how will this transition unfold? Ben Thompson at Stratechery argues that it will mirror the adoption of PCs in the 1980s. It will start in the workplace:

“The vast majority of the consumer market had no knowledge of or interest in computers; rather, most people encountered computers for the first time at work […] once consumers were used to using computers at work, an ever increasing number of them wanted to buy a computer for their home as well […] I suspect that this is the path that virtual reality will take.”

While nearly every consumer knows about Meta (and the metaverse), they still don’t truly know why they need another device, platform, or place to work. Meta is the first mover in creating a device (and an ecosystem) where people can truly work together, wherever they are located.

Early indications seem bearish. The Verge reported that Meta’s flagship app, Horizon Worlds, is buggy, and employees are barely using it. New York Times reporter Brian Chen thought that playing games was “the only reason” to buy a Quest Pro.

However, we’re still in the early innings of adoption in VR. Statista estimates that just 84 million users use VR/AR hardware today — approximately the number of cell phone users in 1995 (91 million), or world wide web users in 1997 (70 million). App downloads on Oculus numbered 10.6 million — the amount that Apple’s app store generated in 3 days.

Adoption might seem slow, but we see momentum building:

Hardware is getting lighter, more comfortable, cheaper and more powerful

Development for VR is becoming easier than ever, with tools such as Unity, Engage, and Unreal Engine

Dedicated VR chips like Qualcomm’s Snapdragon are allowing for HD video and whole-body tracking

5G is coming to enable low-latency streaming and making VR apps more widely available

Retail is experimenting — with firms such as Amazon, Alibaba and Wayfair implementing AR and VR tools for shopping and virtual try-ons

Funding is climbing — 2021 was the second-best year ever for VR/AR venture capital funding, at $3.9B

Immersive learning is one of the “killer apps” of XR… and it’s here now. Training simulations like the VITAL helmet and Super Cockpit were major initial pushes in the history of VR, and history is repeating.

Big corporations like Verison, Boeing, UPS, and Walmart are investing in training applications to simulate going into New York City manholes, building aircrafts, and training store associates to be more empathetic.

Time will tell if Meta is able to convince customers (and the market) of their bet on the metaverse. If so, it could echo the history of XR, starting with specialized military and training purposes before reaching the workplace… giving “out of office” a whole new meaning.

Market Performance

Last week we used the cliché that the Market was like a roller coaster…but in fact, it’s really more like Disneyland’s Space Mountain because Space Mountain is a roller coaster in the dark with the ups and downs, twists and turns are impossible to predict, you just know they are coming.

Boosted apparently by San Francisco Federal Reserve President Mary Daly saying future interest rate increases could come in smaller doses, stocks shot up for the week. The NASDAQ led advancing 5.2%, the Dow was next increasing 4.9% and the S&P was up 4.8%.

Speaking of Space Mountain and roller coaster rides, Liz Truss’ 44 days as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom is hard to fathom how such a disaster happened to such a great Country. It’s hard not to put this in contrast to President Xi’s re-upping for another 5 years but in actuality, he’s likely leader for life.

Some of the pandemic stocks got a booster with Netflix finally seeing a upward turn in subscribers, with 2.4 million net new ones joining last quarter and NFLX was up 13% for the week (but is still down 51% for the year). Zoom, whose $25 billion Market Value is back where it was in January despite its daily users growing from 10 million then to over 300 million today. At its peak, Zoom shares had a market value over $150 million but for the week, Zoom zoomed and advanced 12%. On the other hand, Snap snapped and was down almost 30% after announcing deeper cuts and a flat fourth quarter.

Classically, a 60/40 mix between stocks and bonds was thought to be prudent, and historically that was mainly the case. This year, however, the 60/40 Balanced Portfolio has been clobbered down nearly 35% YTD. Falling equity prices and rapidly rising interest rates were the culprits.

Big Tech has a Big Week coming up with Microsoft, Alphabet, Meta, Apple, Amazon and Intel all reporting between Tuesday and Thursday. Many headwinds including a strong dollar, rising interest rates, uncontained inflation and lowering consuming confidence all have us cautious before we get the actual results.

GSV’s Four I’s of Investor Sentiment

GSV tracks four primary indicators of investor sentiment: inflows and outflows of mutual funds and ETFs, IPO activity, interest rates, and inflation. Here’s how these four signals performed this past week:

#1: Inflows and Outflows for Mutual Funds & ETFs

Total Equity Funds went from (0.11) to (-2.7) from 10/5 to 10/12. This decrease reflects the uncertainty of the recent inflation print (and the ongoing conflict in Ukraine).

#2: IPO Market

The IPO market was dealt a blow this week, as Instacart pushed its much-anticipated IPO to 2023 due to continued market volatility. Meanwhile, Saudi Aramco — after a $48.4 billion profit in Q2 2022 — is rumored to push ahead with an IPO of its energy-trading business.

#3: Interest Rates

The Fed is expected to deliver another 75-basis-point rate hike at its meeting on November 1–2. However, San Francisco Fed Chair Mary Daly said that while markets have priced in a rate hike, people should not expect that “it’s 75 forever” and that existing projections are “thoughtful” and “incredibly data-dependent.” We’ll see…

#4: Inflation

Consumers continue to adjust to the new realities of inflation. While the inflation debate continues to define markets and midterms, credit card spending remains at near-record levels. Bank of America reported 10% more transaction volume in September than last year, while American Express saw travel and entertainment up 57% from last year.

EIEIO — Fast Facts

Entrepreneurship…

1,200 — amount of times the average knowledge worker toggles between apps over the course of the day, equivalent to four hours a week (Source)

8.6 million — amount of small and medium-sized companies in Latin America led by female entrepreneurs (Source)

31% — increase in patent creation at companies where the founder is still CEO (Source)

450 — Web3 startups started in India since 2020 (Source)

$45 billion — deficiency between capital invested and capital demanded for Series B startups — the largest gap ever observed (Source)

Innovation…

$1.7 billion — amount that BMW is investing to build electric vehicles in the US (Source)

3 million — NFT wallets created on Reddit, more than exist on the OpenSea marketplace (Source)

42% — percentage of Americans projected to be monthly voice-assistant users (Source)

$14 billion — amount stolen due to identity theft last year (Source)

$14 billion — amount stolen by crypto scammers worldwide in 2021, a 79% increase from 2020 (Source)

Education…

1.5 million — decrease in students enrolled in college since before the pandemic (Source)

70% — amount of parents worried their children are turning into internet “zombies” (Source)

42% — amount of 9-year-olds who read every day for fun, down from 53% in 2012 (Source)

34 gigabytes — the amount of data and information consumed every day by the average American (Source)

100,000 — the equivalent amount of words heard or read every day by the average American (Source)

Impact…

111 — the amount of hours required for a minimum wage worker to afford a one-bedroom apartment in New York City (Source)

$400 million — Steve Ballmer’s commitment to Black venture capital and private-equity managers (Source)

$85 million — MacKenzie Scott’s donation to Girl Scouts of the USA, the Girl Scouts’ largest even from a single individual (Source)

$1.2 trillion — size of the global impact investing market as of October 2022 (Source)

60 million — the amount of hours that used to be spent commuting saved each day by American workers (Source)

Opportunity…

1.5 million — the amount of paid subscriptions to Substack publications, a 5x increase over the past two years (Source)

95% — percent of jobs that do not require a college degree at AT&T, the #1 company for career mobility (Source)

56% — percentage of directors who think their boards understand carbon emissions well (Source)

26% — percentage of women represented in the C-Suite, up from 20% in 2017 (Source)

4.1 million — amount of registered learners on Coursera in the MENA region, a 61% YoY growth (Source)

GSV’s Big 10

#1 Opinion | Education is the iceberg issue of the midterms

Education is on the ballot. The unions figured out a long time ago that you could control a school board with a minuscule portion of the population’s vote. As Virginia and Florida have proven, education has become a key issue — especially for the coveted suburban female voter.

#2 A Coming-Out Party for Generative A.I., Silicon Valley’s New Craze

If software is eating the world, AI is its teeth. Jasper’s $125M raise and acquisition of Outwrite, Stability AI’s $101M raise, and OpenAI’s rumored raise at a $20B valuation all prove that even in a nasty bear market, generative AI is attracting lots of interest and investment.

#3 purpletutor: How can Artificial Intelligence help in creating disruption in the Edtech industry?

AI and education is expected to grow at a stunning 45% CAGR between now and 2027. With the explosive growth we’re seeing, we’re seeing explosive market caps, led by Grammarly at $13 billion. Accelerated learning, personalized learning, and finding time will all be game-changers for learning.

For more insights on the news in education and workforce upskilling, subscribe to N2K and The Big 10.

Chuckle of the Week

Connecting the Dots & EIEIO…

Old MacDonald had a farm, EIEIO. New MacDonald has a Startup…. EIEIO: Entrepreneurship, Innovation, Education, Impact and Opportunity. Accordingly, we focus on these key areas of the future.

One of the core goals of GSV is to connect the dots around EIEIO and provide perspective on where things are going and why. If you like this, please forward to your friends and subscribe to EIEIO. Onward!

Make Your Dash Count!

-MM

Michael Moe is the founder of Global Silicon Valley, as well as the ASU GSV Summit, GSVlabs, the GSV MBA in Entrepreneurship, and numerous other investing, advisory, and media businesses. Author of Finding the Next Starbucks (Penguin Group, 2007), The Global Silicon Valley Handbook (Hachette, 2017), and The Mission Corporation (RETHINK Press, 2021), Michael’s honors include Institutional Investor‘s “All American” research team, The Wall Street Journal‘s “Best on the Street” award, and “one of the best stock pickers in the country” by Business Week. As CEO of GSV, he led pre-IPO investments in Facebook, Twitter, Snap, Dropbox, Chegg, Spotify, and many more.